The Democratic Party's Strategic Paralysis

A framework for understanding the party’s strengths and its strategic inertia.

The Democratic Party is strategically stagnant. Yes, there are bold voices within it, but the broader apparatus promises little more than national decline masquerading as American exceptionalism.

What is the Party actually going to do for us? What results does it — not just its more charismatic members — promise the American people? How does it intend to deliver?

I understand that Republicans control all three branches of the federal government. But when I step back and take a broader view, I don’t see a powerless Democratic Party. I see one that still holds profound strategic levers.

So why isn’t it wielding them?

Porter’s Five Forces is a framework traditionally used to analyze business competitiveness, but its core idea – understanding the pressures on an organization’s strategy — is just as applicable in politics.

When I apply Porter’s framework to the Democratic Party, I don’t see an institution crushed by opposition — I see one that still holds significant leverage.

America’s political system is famously resistant to third-party challenges, and the structural barriers — like gerrymandering, Electoral College mechanics, and ballot access restrictions — are so daunting that no credible third-party has emerged since the Reform Party thirty years ago (which failed to win a single Electoral College vote).

The list of potential threats to the Democrat/Republican duopoly is speculative to the point of delusion.

Maybe The Rock could do it?

By substitutes, I don’t mean third parties again — I mean a “product” outside the American party system that meets the same need for the voter but in a different way (i.e., a pathway for voter agency that bypasses the party system altogether). I see three alternatives:

Running for office yourself

Volunteering/grassroots organizing

Opting out of American society (e.g., leaving the country or picking a direction and walking into the woods).

While these are valid pathways to engagement or escape, they do not undermine the political might of the Democratic Party.

The major political parties are ostensibly accountable to the American people, but in practice, the average voter’s influence on the Democratic Party’s policy is negligible. The structural barriers for third parties (see above: gerrymandering, Electoral College, ballot access) also limit the influence of the American citizen.

And then there’s the refrain we hear every election cycle: We have to vote for the Democrat, because the alternative — Trump — is an existential threat to the economy, healthcare, democracy, etc., etc., etc. We must vote for whomever the Democrats shove down our throats. Lives depend on it!

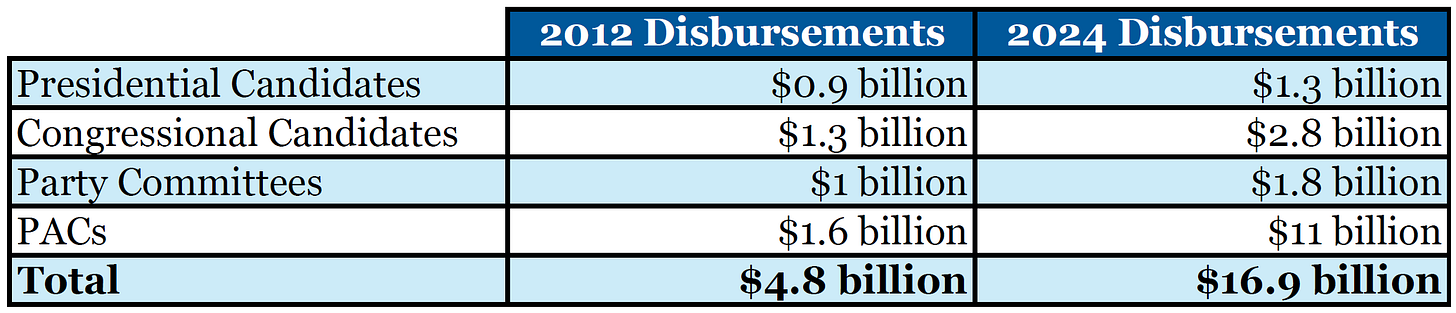

I mentioned in my article two weeks ago that the amount of money raised by congressional candidates has more than doubled in the last decade — from 1.5 billion in 2014 to 3.3 billion in 2024. Almost a two billion dollar increase!

This time, let’s take a more holistic view — comparing the 2012 election cycle (since 2014 didn’t have a presidential election) to 2024. And let’s look at disbursements (i.e., how much was actually spent) rather than donor contributions. (Note: the FEC statistical summaries do not include breakdown by party, so this is inclusive of both Democrats and Republicans).

That’s more than a $12 billion dollar increase in campaign spending across twelve years.

$12 billion dollars!

Inflation can’t explain that explosion – and it’s not like we’ve added more congressional seats or presidents since 2012.

This is a desperate increase in campaign expenses, and candidates everywhere — including incumbents — are desperate to keep pace.

So they need donors. Both parties depend on donors if they want to afford campaign infrastructure, advertising, and staff.

With this surge in spending, the real electorate isn’t the voter base.

It’s the donor class.

This is perhaps the most intense and high-profile rivalry in American life — more entrenched and visible than Coke vs. Pepsi, DC vs. Marvel, or Drake vs. Kendrick. The Democratic and Republican parties are locked in a perpetual, zero-sum competition for power. This rivalry is national, local, ideological, and personal, and it plays out in 24/7 media cycles, legislative trench warfare, and contributes directly to the explosion in campaign spending.

Despite Republicans currently holding all three branches of the federal government, the Democratic Party remains a powerful and entrenched competitor. Just a year ago, they held the presidency. Today, they remain the second most influential political force in the most powerful country in the world. As an enduring institution with deep influence over state governments, urban centers, and major grassroots organizations, the party’s reach extends well beyond the role of opposition.

And they can still mount an opposition. History shows that even as a minority, political parties can shape national discourse and obstruct majority agendas. Republicans did this to great effect during the Obama years.

The balance of power between the two parties may fluctuate, but the Democrats’ institutional influence — and their role in this rivalry — remains formidable. For now.

Despite the Republican Party’s current dominance and the outsized influence of campaign donors, the analysis above shows a Democratic Party that still holds substantial strategic power.

The Democratic Party’s perceived weakness is not rooted in the competitive landscape. If I applied this framework to the Republican Party instead, we’d see them rate the same across the board.

The real issue for the Democrats is not structural weakness. It’s strategic.

The Party lacks vision.

The Party lacks a coherent plan.

The Party lacks strong, unifying leadership that understands how to wield its advantages and attack its vulnerabilities – and it has lacked all of this at least since the end of the Obama era.

Someone needs to figure out how to steer it. Who’s it going to be?